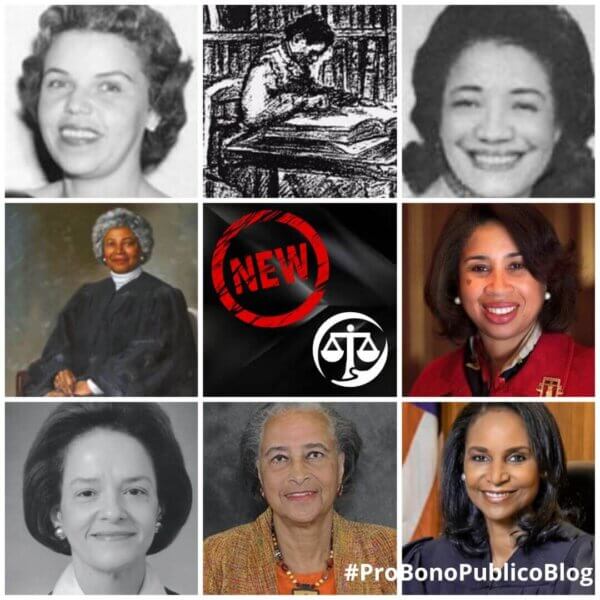

Black Women in the Judiciary

(Pictured from top left, going clockwise) Hon. Marjorie McKenzie Lawson, a possible sketch of Charlotte E. Ray, Esq., Hon. Julia Cooper Mack, Hon. Anna Blackburne-Rigsby, Hon. Anita Josey-Herring, Pauline Schneider, Esq., Hon. Judith Ann Wilson Rogers, and Hon. Norma Holloway Johnson)

By Stephon Woods

On Friday, February 25, 2022, President Joseph R. Biden fulfilled a promise to nominate the first Black woman as a justice to the U.S. Supreme Court if given the opportunity. Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s historic nomination is momentous, not just because history’s being made, but also in recognition of the barriers Black women must overcome in entering and succeeding in the legal profession and, more specifically, on the bench.

The statistics are staggering, especially in the judiciary. According to the 2021 National Association for Law Placement’s (“NALP”) Report on Diversity in U.S. Law Firms, Black women account for 3.17% of associates at U.S. law firms, which represents a modest increase of 0.13% from the previous year (2020 NALP Report on Diversity). These statistics certainly do not improve when we look at the makeup of top positions in the legal profession, such as law firm partners. According to the same report, in 2021, Black women accounted for less than 1% of all partners in U.S. law firms. Given these statistics, it comes as no surprise that the federal judiciary is equally lacking in representation of Black women judges, with less than 2% of judges who have served as federal judges being Black women, according to a biographical database by the Federal Judicial Center.

With this context, I could focus the rest of this piece on the many barriers Black women face to becoming judges. But what I choose to do instead, as we close out Black History Month (or, as I like to call it, the kick-off to a year-round celebration of Black History) and in the midst of Women’s History Month, is to celebrate the accomplishments of Black women in the legal profession who have ascended in their careers to be well-respected jurists despite the odds against them. There is no doubt that diversity in the legal profession, specifically on the bench, makes a huge difference in the practice of law and the lives of litigants. Many studies and reports, such as the American Bar Association’s Commission on the 21st Century Judiciary titled “Justice in Jeopardy,” have been published that highlight how diversity fosters public trust in the court system. When people feel they have suffered injustice, whether when experiencing discrimination in employment or housing, or being victims of police brutality, seeing a Black woman or any person of color presiding over their case in court innately gives assurance that their issues will be heard fairly and without bias. This rings true for the client community many pro bono and public interest lawyers represent, which is a critical component of access to justice – ensuring everyone’s perspectives are heard and appreciated.

I’d like to take a moment to recognize some of the Black women who have played an instrumental role in our local judicial system. These history-making women have disrupted the status quo to create an environment where litigants can feel the court system is about justice, fairness, and representation. There is no doubt that their paths to the bench have and will continue to inspire many generations of lawyers, not just women but all genders.

Marjorie McKenzie Lawson: Our celebration of Black women jurists begins with the first Black female judge in Washington, D.C. In 1962, she was appointed to the Juvenile Court of the District of Columbia as an associate judge by President John F. Kennedy, whose campaign she worked on as the civil rights director. Prior to her judicial appointment, she established herself as a well-respected lawyer working on real estate development to address urban decay in cities across the United States. Judge Lawson went on to serve in several other capacities, including on President Kennedy’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity, as vice chairman of the District Crime Commission, and as the U.S. representative to the United Nations Economic and Social Council. Towards the end of her career, she co-founded the Model Inner City Community Organization, which sought to create public housing in the District of Columbia.

Julia Cooper Mack: In 1975, Judge Julia Cooper Mack became the first African American woman to be appointed to the District of Columbia Court of Appeals, which is the court of last resort for the District of Columbia. President Gerald Ford’s appointment of Judge Mack was historic for a second reason – Judge Mack became the first Black woman to serve on any court of last resort in the United States. Prior to her appointment to the D.C. Court of Appeals, she served in various federal attorney positions, including as a trial attorney with the U.S. Department of Justice and in the general counsel’s office at the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Judge Mack also embodied how representation can make a difference for future generations of lawyers, as one of her first law clerks was Allyson Kay Duncan, who went on to become the first Black woman appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

Norma Holloway Johnson: Judge Norma Holloway Johnson made history in 1997 when she became the first Black woman to serve as Chief Judge of any United States District Court, more specifically the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. She had already been a judge in the D.C. Circuit for 17 years, and prior to that had served as an Associate Judge on the District of Columbia Superior Court. At the start of her career, she worked in private practice in Washington, D.C., then as a trial attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice, and later as Assistant Corporation Counsel (later retitled Assistant Attorney General) for the District of Columbia.

Judith Ann Wilson Rogers: Judge Judith Rogers has led a history-making career since graduating Harvard Law School as one of 15 women in a class of over 500 students. She currently serves as a Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Her 1994 appointment made her the fourth woman and first Black woman to serve in this capacity. She succeeded the Honorable Clarence Thomas, the second Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice and now the longest-serving member of the Court, who succeeded the Honorable Thurgood Marshall, the first Black Judge on the U.S. Supreme Court. Prior to that, she was an Associate Judge of the District of Columbia Court of Appeals and served as Chief Judge from 1988 to 1994. She held many positions and worked on many critical projects throughout her career. Her positions include Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, staff attorney at the San Francisco Neighborhood Legal Assistance Foundation, and trial attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice. She helped develop the District of Columbia Home Rule Act, which was passed in 1973 and continued to work on legislative affairs in the D.C. government until 1979 when she became the first female Corporation Counsel (now known as the Attorney General) for the District of Columbia.

Last, but certainly not least, I must acknowledge the two Black women who lead the District of Columbia’s trial and appellate courts: Chief Judge Anita Josey-Herring and Chief Judge Anna Blackburne-Rigsby, respectively. Judge Josey-Herring was appointed to the D.C. Superior Court in 1997 by President Bill Clinton, and in October 2020 she was sworn in as the Chief Judge of the trial division. Prior to serving on the bench, she worked as a staff attorney for the District of Columbia Public Defender Service in both the trial and appellate division. Judge Blackburne-Rigsby was sworn in as Chief Judge of the D.C. Court of Appeals in March of 2017. Prior to that, she served as an Associate Judge on the same Court and earlier served on the D.C. Superior Court from 2000-2006. She began her career in private practice and later joined the D.C. Office of the Corporation Counsel (now the Office of the Attorney General), where she served as Special Counsel and later as Deputy Corporation Counsel of the Family Services Division.

Honorable Mentions: Two honorable mentions worthy of celebration (because let’s face it – Black women deserve all the accolades) that are not jurists but have served the legal community in significant ways are Charlotte E. Ray and Pauline Schneider. Charlotte Ray was a woman of many firsts, such as the first Black woman lawyer in the United States, the first woman admitted to the District of Columbia Bar, and the first woman admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia (now the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia). Pauline Schneider is an accomplished attorney and the first Black woman to serve as president of the D.C. Bar Association. She also was the first woman to make partner at Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe, and prior to that served in District government and in the White House for President Jimmy Carter. She practices primarily in public finance.

While this list is just a representation of the many amazing Black women who have padded our local judiciary with impressive accolades and accomplishments, I hope their stories inspire us all to achieve greatness.

Stephon Woods is a Washington Council of Lawyers Board Member and co-chair of our Communications Committee.